Using a variety of sources, CERAC has been closely monitoring the FARC’s ceasefire that began on December 15th and ended this past Wednesday. Though by and large upheld, it was far from perfect.

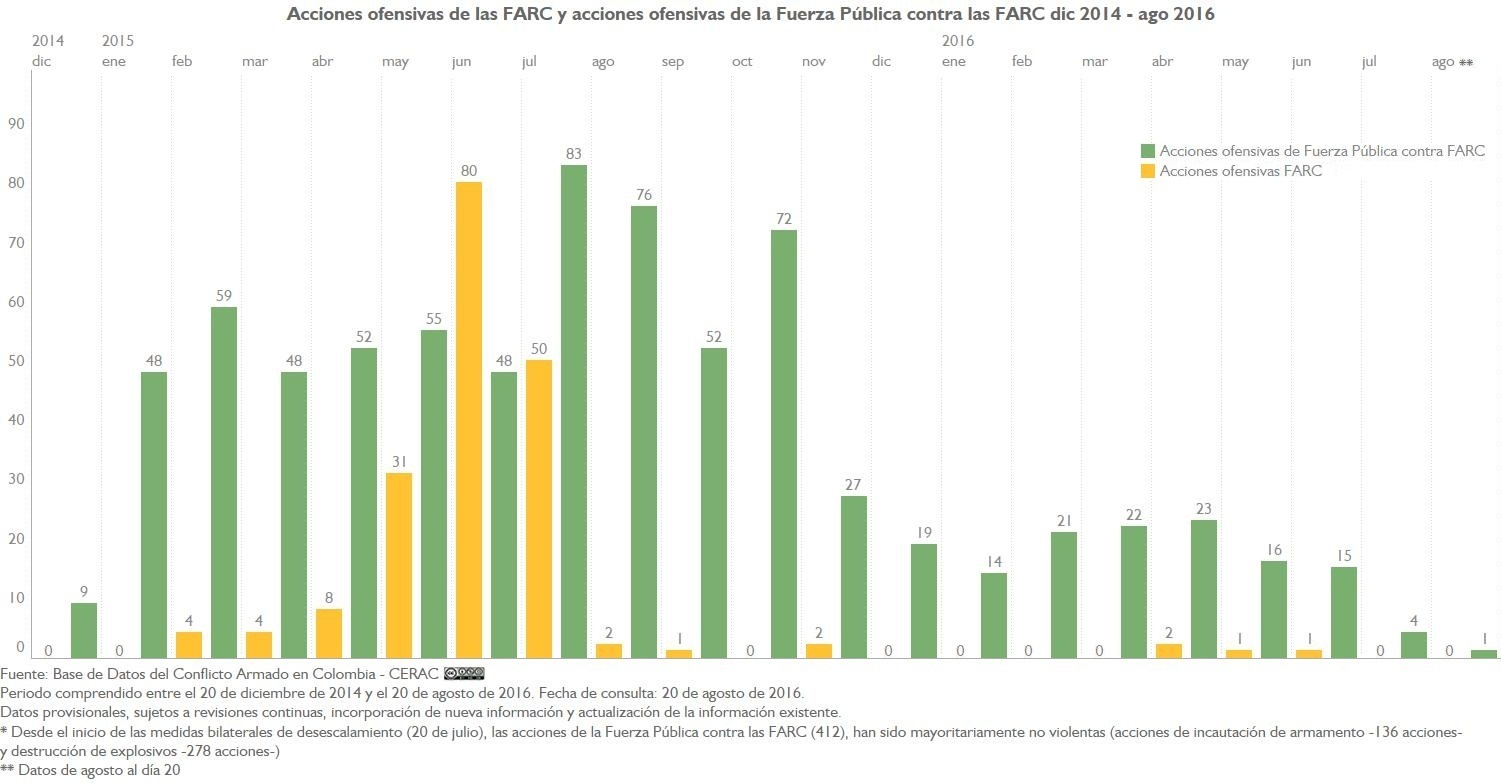

Admittedly, violence related to the conflict did take a precipitous drop: during the 30-day truce, the FARC was reported as responsible for only two deaths. Yet that did not prevent them from taking part in numerous armed activities – slightly more, in fact, than the same period on the previous year. Compared with the monthly average of FARC’s armed activities over the previous three years, the ceasefire represents a 65% decrease in activity – a similar reduction to the previous ceasefire.

Yet the decrease in activity was also followed by a diversification of tactics. Rather than target military objectives or urban conglomerations – typical strategies of the FARC that saw deep reductions – the guerrilla group increased the number of threats it made and continued to exacerbate displacement in rural communities.

| The Ceasefire In a public statement issued on 8 December, the FARC announced a unilateral ceasefire from 15 December – 15 January – a cessation of hostilities to be undertaken by all of its guerilla units, fronts and columns. It differed from that of 2011, when after a long and protracted month of negotiations, a two-month ceasefire was enacted from 20 November 2012 – 20 January 2013. |

Monitoring levels of violence and unilateral action: the FARC take a step back

The FARC engaged in twelve unilateral actions during the most recent ceasefire, a slight decrease on the previous year (when twelve were recorded during the same period) – though an increase on 2011, when there was no concomitant truce.

If the goal of the FARC is to demonstrate its capacity to exercise violence at will, then hostilities undertaken in the past month only delegitimize its stated purpose. Or, worse, betray incapacity to keep its troops in check or ensure that military decisions made at the peace table are carried out on the ground. Indeed, actions taken during the ceasefire are seen by some as a broader disintegration of the command structure. While they represent less of an organizational collapse than analysts have previously predicted (or hoped for), they belie the claim that the FARC´s leadership in Cuba has complete control over its forces on the ground.

Despite these setbacks, the ceasefire has had a positive impact upon the overall status of the Colombian conflict in reducing the level of violence the FARC is willing to employ. Compared to the monthly averages of 2013 – or the thirty days preceding the ceasefire – the period of the ceasefire saw a 65% drop in violent actions taken by the FARC. (There were 38 such actions taken between 15 November – 15 December and October 2013 alone saw 70, the most that year). One should bear in mind, however, that the lull in FARC-committed violence did not prevent other armed groups from continuing as before.

The Victims:

Compared to the ceasefire of 2012-13, in which a policeman, a soldier and a civilian were killed, that of 2013-14 has only seen two deaths at the hands of the FARC – a soldier and a civilian. The same period in 2011 saw two civilian deaths. More starkly, in the month before the ceasefire, the FARC was responsible for eight deaths: four civilians, two soldiers and two policemen. Each of these figures demonstrates a marked decrease not only in the degree of violence, but in its volume and intensity as well.

That being said, the number of non-lethal victims – both civilian and combatant – increased during the ceasefire. Whereas the previous ceasefire witnessed only four injuries, two civilian and two soldiers, the most recent saw ten: five civilian, four police and one soldier. All the same, this level of violence is still a marked decrease on 15 November – 15 December 2013, when thirty people were injured, including ten civilians, fifteen soldiers and five policemen.

While the continuing number of victims of the FARC over the past month is less than ideal, this reduction in fatal violence is a direct result of the ceasefire and an important step in the right direction. Indeed, the figures themselves are testimony to the strategic changes undertaken by the FARC during this period.

| A helicopter crashes in Anorí On 10 January a helicopter operated by the Sociedad Aeronáutica de Santanter S.A. crashed to the ground killing five people – XX of whom were members of the Colombian Army. Reports vary as to what transpired that day, but the official version claims an investigation is still under way; the company that owned and operated the aircraft claims there were neither mechanical problems nor adverse weather conditions leading up to the fall. Yet an outpouring of photographs on social media sites show scattered remains of the aircraft impacted by what appears to be missile-fire: if so, a clear signal of the possible involvement of armed groups in the helicopter’s demise. To be sure, Anorí has historically been a haven of the ELN, but in recent times has been known to harbour violent neoparamilitaries such as the Urabeños, in addition to the FARC.The difficulty in determining whether or not the helicopter crash was the product of a military strike lies in the fact that it was performing a civilian mission: the troops aboard it were partaking in a humanitarian exercise – the rescue and transportation of a wounded soldier. |

Categorizing the violence: an increase in threats and explosions

The period of the ceasefire witnessed a visible change in the nature of violence employed by the FARC. Targeted explosions and a marked uptake in threats composed the majority of unilateral violent action taken. Of eleven such events during the ceasefire, three were explosions and three were threats.

The number of targeted explosions recorded was the same as that of the previous ceasefire. On the one hand, this represents a noticeable decrease on the month leading up to the ceasefire, which saw six explosions carried out by the FARC. On the other hand, there are discernable periods when the absence of a ceasefire is met with the absence of certain kinds of violence: there was only one targeted explosion between December 2011 and January 2012, a period when no ceasefire was in effect.

The three threats of the ceasefire were an increase on the two reported during the previous truce. Yet in conjunction with the reduction in explosions, threats were also down on the previous month, from four to three. That being said, the nature of these threats was often collective: on two separate occasions, massive civilian displacements were the result of threats stemming from the FARC. During the same period from 2011-12, no threats or civilian displacement were recorded.

It’s hot in Antioquia

Whereas 2012 witnessed a high concentration of violent activity in the departments of Cauca, Norte de Santander and Huila, this year saw a concentration of action – admittedly less than in the previous ceasefire – in the departments of Antioquia and Caquetá.

| Analysis Periods of negotiation cause the FARC to regulate its actions and modify its immediate strategies. Indeed, ceasefires are opportunities – if not obligations – for the FARC to improve its public image and bolster its credentials before the domestic and international communities as an organization committed to peace and the protection of human rights (DIH?). They also serve as a mechanism for reigning in their own forces. As such, the most recent ceasefire is not only a step in the direction of peace, but an opportunity for the FARC’s command structure to exert control over its vast network of sub-groups and sub-units, from the Secretariat on down to the lowest foot soldier in field.The FARC’s (in) ability to act collectively during periods of ceasefire does more than expose the group’s internal divisions: it reveals deeper ruptures that are brought to the surface and exacerbated by the peace process. To give but one example, any demobilization agreement will necessarily affect certain sub-units’ rent-seeking activities – mining and narco-trafficking being the most common.That being said, this report is not suggesting that the peace process has lead to any systemic crisis within the organization’s command structure, or imperilled its ability to speak with one voice at the negotiating table. Nor has it inhibited the group from acting in unison once an agreement is reached. Whatever disagreements arise from such exchanges are marginal in the broader geo-political scheme of things. |

An alternative military strategy?

Throughout the ceasefire, the Armed Forces of Colombia have taken a different strategic approach to how they engage the FARC. Though Antioquia has traditionally been the focus of military operations against the guerrilla organization, the state is also taking the fight to southwestern departments such as Putumayo, Caquetá and Valle del Cauca. Moreover, the Armed Forces have also recently engaged the FARC in the east of the country – Arauca, Caquetá and Meta, to be precise.

If nothing else, the ability of the Armed Forces to concentrate their efforts against guerrilla fronts such as the Bloque Sur, the Bloque Occidental and the Bloque Jorge Briceño – each of which might be against the peace process – is a telling indication of developments to come.